A file photo of a tanker, seen off the port of Karystos on the Aegean Sea island of Evia, Greece, Friday, May 27, 2022. | Photo Credit: AP

Explained | Why are Turkey and Greece at odds over islands in the Aegean Sea?

Greece and Turkey have had long-standing rival claims over the Aegean territory, even finding themselves on the brink of war over the issue in the past …

The story so far: Warning Greece “to stay away from dreams and actions” that it would later regret and urging it “to come to its senses”, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on June 9 told the country to demilitarise islands in the Aegean Sea. Mr. Erdoğan added that he was “not joking” with the admonition.”

Turkey alleges that Greece has been building a military presence in violation of international treaties that guarantee the unarmed status of the Aegean islands. Meanwhile, Greece maintains that Turkey has deliberately misinterpreted the treaties, adding that it has legal grounds to defend itself.

In late April, the two NATO allies traded barbs about airspace violations over the Aegean Sea. Greece informed NATO about a series of overflights in the Aegean Sea by Turkish fighter jets. Turkey retaliated by saying that Greece was the one “instigating” tensions by carrying out “provocative flights” near Turkish coasts.

Why is the Aegean Sea at the centre of Greco-Turkish ties?

Map of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea, spanning over two lakh square kilometres, is an arm of the Mediterranean Sea. It is located in the East Mediterranian Basin with the Greek peninsula to its west and Anatolia (consisting of the Asian side of Turkey) to its east. There are more than a thousand islands in the Aegean Sea, almost all Greek, and some within two kilometres of mainland Turkey or the Turkish west coast.

Greece and Turkey have been regional adversaries on a host of issues concerning the Aegean sea since the 1970s, both asserting rival claims over their borders in the Sea. They came to the brink of war in 1996 over a pair of uninhabited islets in the Aegean Sea, referred to as the Imia islets in Greece and as Kardak in Turkey. A Turkish cargo ship had run aground in Imia in December 1995 and both countries rushed to salvage it. Turkey rejected Greece’s help and its sovereignty over Imia. Shortly after, both countries moved their navies towards Imia, resulting in a standoff that spilled over into January of 1996. The issue attracted international concern as both countries began to mobilise their forces for war, however, global intervention prevented further escalation.

Over the decades, attempts at resolving disagreements over the Aegean Sea have seen the involvement of multiple actors like the United Nations, the United States, European countries, the International Court of Justice, and NATO.

What do international treaties say about Aegean islands?

The Lausanne Treaty of 1923 was signed at the end of the First World War to settle the conflict between Turkey (the successor of the Ottoman Empire) and the Allied Powers including Greece. The Treaty defined the boundaries of Turkey and Greece, and several islands, islets and other major territories in the Aegean Sea beyond three miles from the Turkish coast were ceded to Greece, with the exception of three groups of islands. Under the terms of the Treaty and the Lausanne Convention of 1923, Greece was obligated to keep the islands demilitarised. The Treaty also opened up civilian shipping passage in the Turkish Straits and mandated Turkey to demilitarise the straits. Turkey also ceded Cyprus to the British.

At the end of the Second World War, as part of the Paris Peace Treaties of 1947, the Dodecanese Islands (a group of 12 islands in the Aegean Sea) were given to Greece, again with the obligation of permanent and total demilitarisation. They had been ceded to Italy in 1923.

While Turkey recognises both these treaties, Greece accuses it of wrongly interpreting them, and argues that the 1936 Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits superseded the Lausanne Treaty on the Straits, as it gave Turkey the power to militarise the Turkish Straits, hence nullifying the obligation upon Greece to demilitarise the Aegean Islands.

What are the issues that have caused friction over the Aegean Sea?

Turkey and Greece have long sparred over the extent of their respective territorial waters in the Aegean, the determination of continental shelves, airspace, Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), militarisation, and sovereignty of certain islets.

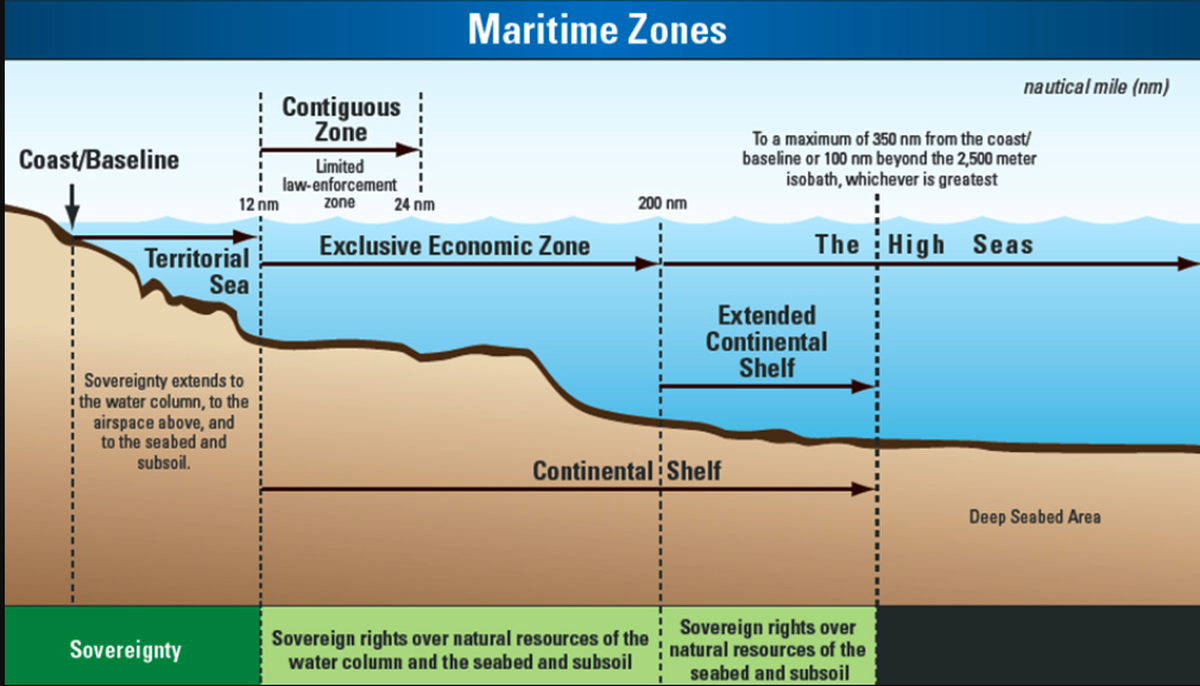

Maritime zones under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) | Photo Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (American govt agency), noaa.gov

Territorial seas

In 1995, Greece ratified the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which provides a legal framework to recognise the limits of maritime zones of coastal nations. While over 160 countries are party to the Treaty, Turkey did not sign it as it did not favour its interest in the Aegean Sea.

According to the UNCLOS, the sovereignty of a coastal country extends “beyond its land territory and internal waters” to an “adjacent belt of sea, described as the territorial sea”. A country’s territorial sea extends to 12 nautical miles (nm) from the baseline of its coast, and it has sovereign rights over it. (One nautical mile is equal to 1.1508 land-measured miles or 1.852 kms.)

Presently, Turkey claims a territorial sea of six nautical miles and has not exercised its claim over the 12 nautical miles from its coast in the Aegean Sea. After the Greek Parliament adopted the UNCLOS in 1995, Turkey retaliated by authorising its government to take necessary steps including military action, if Greece extended its rights to 12 nm. In 1974, in a separate Aegean Sea-linked issue, Turkey had formally said that if Greece fully extended its territorial waters, it would count as a casus belli (cause of war).

Ankara argues that if Greece extends its territorial waters it would have control over two-thirds of the Aegean Sea, depriving Turkey of its basic access to international waters and trade routes.

Continental shelves and Exclusive Economic Zones

In geological terms, the continental shelf is defined as the seabed and subsoil that is the prolongation of a country’s landmass, extending beyond its territorial sea. The Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is a zone in which a country has special rights to exploration, use of natural resources, wind and hydro-power generation, and other economic activities like laying of pipelines, fishing and so on.

As per the UNCLOS, the continental shelf extends to 200 nautical miles from the country’s coastal baseline but is within its continental margin. A country has sovereign rights over the natural resources in the water and the seabed and soil within its continental shelf. EEZs also extend to 200 nm from the coastline.

Athens argues, citing UNCLOS provisions, that every Greek island in the Aegean generates its own continental shelf, which would mean that the Greek Continental Shelves extend to Eastern Greek islands near the Turkish Coast. Meanwhile, Ankara contends that the continental shelf border in the Aegean is the median line between the coasts of the two countries and should be determined on an equitable basis.

Since the 70s, Turkey and Greece have had disagreements over their overlapping continental shelves and over offshore natural resources like gas and minerals held by these shelves.

In 2020, tensions flared between the two countries when Turkey sent its seismic research vessel Oruc Reis to map potential drilling opportunities for oil and natural gas near the Greek island of Kastellorizo. A Turkish naval ship collided with a Greek naval ship while both were shadowing the Oruc Reis. The research vessel later returned to Turkish shores.

Turkey maintains that it will undertake exploratory work in the areas it lays claims to as there is no bilateral agreement between the two countries delimiting their continental shelves. Ankara and Athens have also signed deals in the last couple of years creating conflicting EEZs with countries like Libya and Egypt respectively.

Militarisation

Right now, Turkey has cited the Lausanne and Paris treaties, arguing that Greece is violating them by increasing its military presence in the Aegean Islands.

Meanwhile, Greece argues that some of the islands, which have been garrisoned for decades, have troops because they’re in close proximity to the Izmir coast, where Turkey has deployed a large landing force called the Fourth Army, which in theory, makes it capable of seizing Greek Islands. Athens argues that it has a military presence in such islands for the purposes of self-defence. After Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in the 1970s, Greece militarised the Dodecanese Islands near Turkey for defensive purposes.

Presently, for instance, the Greek islands of Rhodes, Kos, and Lesbos in the Aegean Sea near the Turkish coast would meet the description of militarised, according to the Associated Press.

Airspace violations

UNCLOS states that a country has sovereign rights over the airspace above its territorial sea. Currently, Greece claims six nm of territorial sea in the Aegean, starting from its coast. Hence, its internationally recognised airspace over the Aegean is also up to six nm.

Alleged violation of airspace over the Aegean Sea has also been a bone of contention between the two countries. Both Greece and Turkey have alleged that the other is carrying out flights near or over their coasts. As mentioned earlier, Greece has taken the matter to the NATO, while Turkey has said that Greece is the one instigating tensions by flying near its coastline.